By John P. Bluemle

What have those geologists been drinking? First of all, the word "moraine" is an 18th-century French word that simply means a heap of earth or stony debris. I don't know when the term was first used to refer to glacial deposits. I'll explain the "dead" part later.

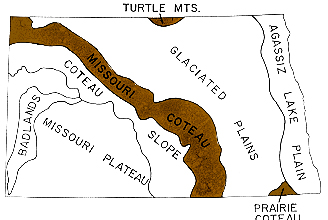

Fig. 1. Areas where dead-ice moraine is found in North Dakota. The dark brown areas are the Missouri Coteau, the Turtle Mountains, and the Prairie Coteau.

Dead-ice moraine is also referred to as "hummocky collapsed glacial topography" or "stagnation moraine." It is a rugged landscape that formed as the last glaciers were melting at the end of the Ice Age, between about 12,000 and 9,000 years ago. The most extensive area of dead-ice moraine is found on the Missouri Coteau, which extends from the northwest corner to the south-central part of the State. Other extensive areas of dead-ice moraine are the Turtle Mountains in north-central North Dakota and the Prairie Coteau in the southeast corner of the State near Lidgerwood ("coteau" is French for "little hill"). The landforms of the Turtle Mountains are identical to those on the Missouri Coteau and Prairie Coteau, but the Turtle Mountains have a woodland cover, the result of several inches more precipitation each year than the other areas.

North Dakota's vast tracts of dead-ice moraine generally make for poor farmland as they are rough, bouldery, and undrained. They do, however, include a lot of excellent rangeland and thousands of undrained depressions - lakes, ponds, and sloughs known collectively as prairie potholes - that serve as important nesting and feeding areas for waterfowl (the so-called North Dakota "duck factory"). The dead-ice moraine of the Missouri Coteau is essentially undrained, except very locally. No rivers run through it. No streams flow all the way through the Turtle Mountains or for any distance through or across the Missouri or Prairie Coteau either.

Dead-ice moraine formed when the glaciers advanced against and over steep escarpments as they flowed onto the uplands. The land rises as much as 650 feet in little more than a mile along parts of the Missouri Escarpment, which marks the eastern and northeastern edge of the Missouri Coteau. Similar prominent escarpments border the Prairie Coteau and the Turtle Mountains, especially the west side of the Turtle Mountains near Carbury. When the glaciers advanced over these escarpments, the internal stress that resulted in the ice caused shearing. The shearing brought large amounts of rock and sediment from beneath the glacier into the ice and to its surface.

Eventually, as the Ice Age climate moderated, the glaciers stopped advancing and stagnated over the uplands (they "died"). As the stagnant glaciers melted, large amounts of sediment that had been dispersed through the glacier tended to accumulate on top of the ice, which was several hundred feet thick. This thick cover of sediment helped to insulate the underlying ice so that it took several thousand years for it to melt. Our geologists have determined that stagnant glacial ice continued to exist in the Turtle Mountains and on the Missouri Coteau until about 9,000 years ago, nearly 3,000 years after the actively moving glaciers had disappeared from North Dakota.

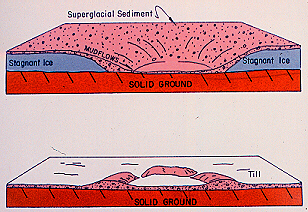

In places where the debris on top of the ice was thickest, the glacier melted most slowly. Over nearby areas, where little or no insulating debris covered on the glaciers, melting was rapid and the land was entirely free of ice 12,000 years ago. As the stagnant ice on the uplands slowly melted, and the glacier surface became more and more irregular, the soupy debris on top of the ice continually slumped and slid, flowing into lower areas, forming the hummocky, collapsed glacial topography - dead-ice moraine - found today over the Turtle Mountains, Missouri Coteau, and Prairie Coteau.

As the stagnant glacial ice melted, and debris slid from high areas to lower ones, a variety of unusual features resulted. Long ridges formed when sediment slid into cracks in the ice. Such ridges may be straight or irregular, depending on the shape of the cracks. In some places, streams followed the cracks, resulting in eskers. In other places, mounds of material collected in holes and depressions in the ice and ring-shaped hummocks ("doughnuts") formed if the mounds were cored by ice. When the ice cores melted, the centers of the mounds collapsed, forming circular doughnut-shaped ridges.

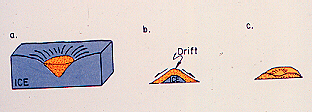

Fig. 2. Diagram showing how a "doughnut" forms.

Wherever part of the covering of debris slid off an area of ice to a lower place, the newly exposed ice melted more quickly, transforming what had been a hill into a hole or depression. Such reversals of topography continued until all the stagnant ice eventually melted.

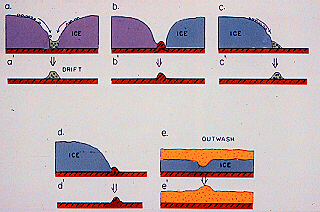

Fig. 3 Diagram showing how various kinds of disintegration trenches form.

Many more depressions formed when buried or partly buried isolated blocks of glacial ice melted, causing the overlying materials to slump down. Geologists refer to these depressions as kettles. Kettles are also found in areas that were not covered by thick stagnant ice, but here they are generally much smaller and resulted when isolated blocks of buried ice melted. Today, kettle lakes, commonly known as prairie potholes or sloughs, are located in the depressions between the hummocks.

In places, the insulating blanket of debris on top of the stagnant glacial ice was so thick that the cold temperatures of the ice had little or no effect on the surface of the ground. Trees, grasses, and animals established themselves on the debris on top of the stagnant ice.

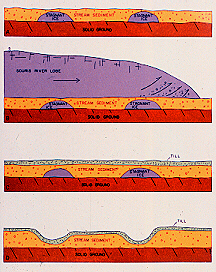

Fig. 4. Diagram showing how other kinds of disintegration trenches form.

Surrounding the lakes and streams, the debris on top of the stagnant glacier was forested by spruce, tamarack, birch, poplar, aquatic mosses, and other vegetation, much like parts of northern Minnesota today. This stagnant-ice environment in North Dakota 10,000 years ago was in many ways similar to stagnant, sediment-covered parts of certain glaciers in south-central Alaska today. Fish and clams as well as other animals and plants thrived in the lakes. Wooly mammoths, elk and other large game roamed the broad areas of forested, debris-covered ice.

Fig. 5. Diagram showing how a ringed lake forms in dead-ice moraine.

I imagine that prehistoric people lived on the insulated glaciers in North Dakota 10,000 years ago without realizing the ice lay only a few feet below. If they did realize it, they probably accepted it as a normal situation (and I suppose it was normal at that time). Eventually, all the buried ice melted, and all the materials on top of the glacier were lowered to their present position, resulting in the hilly areas of dead-ice moraine we see today.

Fig. 6. Photo of a debris-covered and forested glacier. The Martin River glacier in Alaska.

Fig. 7. Dead-ice moraine in Stutsman County.

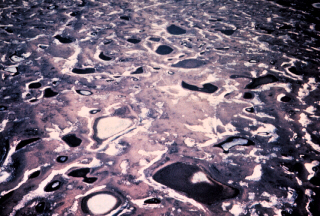

Fig. 8. Air view of the Turtle Mountains.

Fig. 9. Air view of dead-ice moraine in Stutsman County.

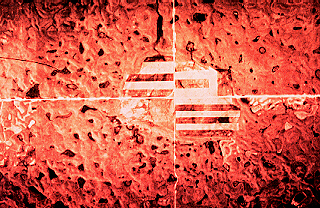

Fig. 10. Typical dead-ice moraine in Ward County.

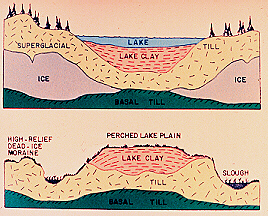

Fig. 11. Perched lake plain near McClusky, in Sheridan County.

Fig. 12. Diagram showing how an elevated (perched) lake plain forms.