|

|

|

John W. Hoganson & Johnathan M. Campbell

North Dakota Geological Survey

600 East Boulevard

Bismarck, North Dakota 58505

Brian R. Austin

State Historical Society of North Dakota

612 East Boulevard

Bismarck, North Dakota 58505

For information on obtaining the actual Education Trunk for your classroom, contact:

Henry Duray

Icelandic State Park

13571 Highway 5

Cavalier, ND 58220

(701) 265-4561

isp@state.nd.us

Introduction

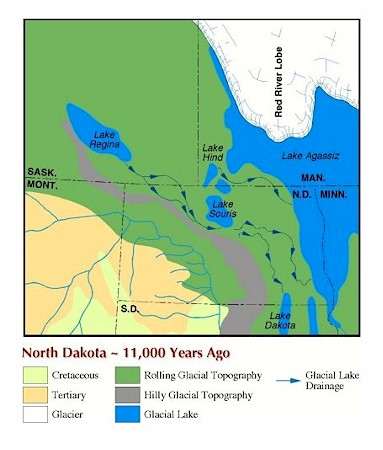

The Geology and Prehistoric Life of the Rendezvous Region traveling education trunk, accompanying CD and this web site are meant to provide information about the geology and paleontology of Cavalier and Pembina Counties, North Dakota. This area is often referred to as the Rendezvous Region because large rendezvous were held there during the fur trade era. The Rendezvous Region is one of the most scenic areas in the state, and it is also one of the most interesting areas from geological and paleontological perspectives. The oldest rocks in North Dakota are exposed in the Pembina Gorge and North Dakota's oldest fossils are found in those rocks. The rocks and fossils entombed in them provide evidence that North Dakota was covered by shallow seas from about 90 to 80 million years ago and that these seas were teeming with life. The last Ice Age, that ended just a few thousand years ago, is documented by landforms produced by glaciers in the Rendezvous Region. Warming of climate, which resulted in melting of glaciers at the end of the Ice Age, produced glacial Lake Agassiz. Lake Agassiz covered the Red River Valley. The terrain is extremely flat in most of Pembina County because the area used to be the bottom of this lake. Beach ridges, the shorelines of Lake Agassiz, are still present in western Pembina County.

Funding for production of the Geology and Prehistoric Life of the Rendezvous Region educational materials is from a restitution that was paid to the State of North Dakota after a fossil site was inadvertently destroyed in the Pembina Gorge. In 1996, a promising fossil site was bulldozed, without authorization, during road construction activity. Because this site is located on land owned by the State of North Dakota, destruction of the site violated North Dakota's Paleontological Resource Protection Act. Collecting fossils of vertebrate animals found on state owned land in North Dakota is prohibited without a permit issued by the North Dakota Geological Survey. The reason fossils are protected by law is because they are an important part of North Dakota’s natural heritage. If we did not find the fossil remains of plants and animals that lived in the prehistoric past, we would never know that they ever existed. Fossils are also protected on federally managed land in North Dakota. Fossils found on state and federal public lands belong to all of us and public land managers have a responsibility to make sure that they are preserved.

The North Dakota Geological Survey, North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department, and State Historical Society of North Dakota collaborated in production of the Geology and Prehistoric Life of the Rendezvous Region education materials

Geology

Introduction

Geology is the study of the planet Earth. The science of geology is divided into two major branches. Physical Geology is the study of the materials (minerals, rocks, soil, etc.) of which the Earth is made, the processes that act on these materials, and the products formed by these processes. It is concerned with the processes and forces involved in developing the landforms that we see on the surface of the Earth. Historical Geology is the study of the evolution of the Earth and its life forms from its origins to the present day.

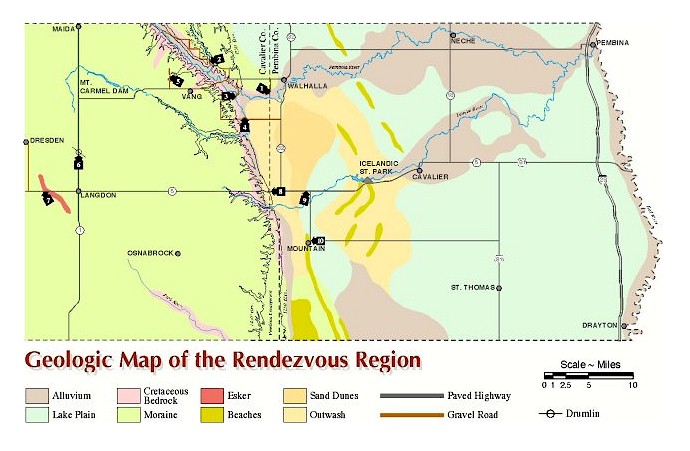

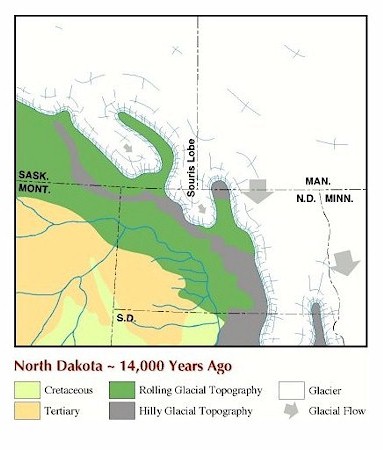

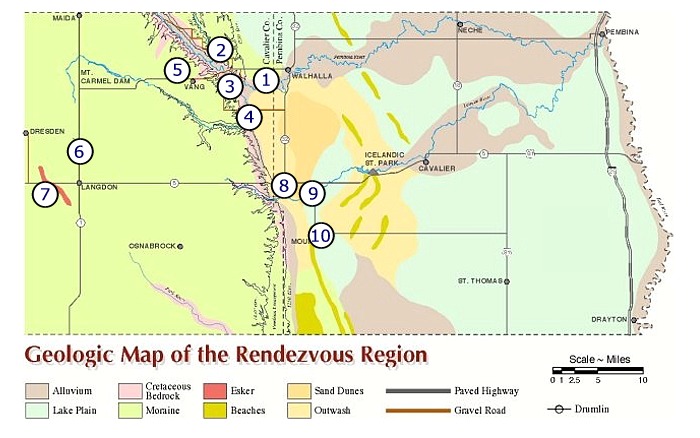

Nearly the entire surface of Cavalier County consists of gently rolling to undulating terrain and is underlain by sediments deposited during the last advance of glaciers into the Rendezvous Region about 12,000 years ago (Map 2). Subtle landforms were produced by these glaciers. The Pembina Escarpment, along the eastern edge of Cavalier County, marks the eastern edge of this glaciated plain. East of the escarpment is the Red River Valley, which is the former floor of glacial Lake Agassiz that occupied the valley about 9,000 years ago (Map 3). The extremely flat Lake Agassiz basin terrain of Pembina County, one of the flattest areas in the world, is interrupted in the western part of the county by low, elongate hills that were Lake Agassiz beaches.

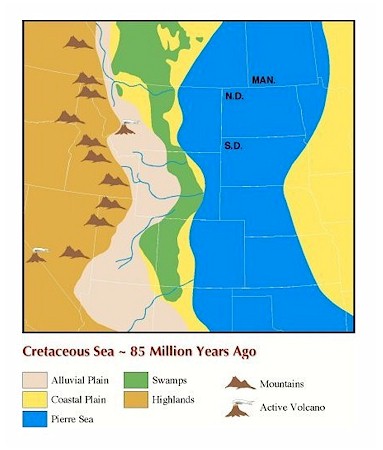

Cretaceous rocks that underlie the glacial deposits in the Rendezvous Region are exposed where rivers, primarily the Pembina River and its tributaries, have cut through the glacial deposits, primarily in the Pembina Gorge (Pembina Escarpment diagram). These Cretaceous rocks were deposited in oceans that covered the area between about 90 million and 80 million years ago (Map 4). The rocks contain fossils of the animals that lived in those oceans.

Pembina River Gorge Overlook

Geology Site 1 - The Pembina River has eroded through glacial sediments and Cretaceous bedrock to form the Pembina Gorge, one of the most scenic areas in North Dakota. View is to the southeast from Tetrault Overlook west of Walhalla.

Walhalla Mosasaur Site

Geology Site 2 - At this road cut, the Cretaceous Niobrara Formation is overlain by the Pembina Member, the lowermost member of the Pierre Shale in the area. These rocks were laid down in oceans that covered most of North Dakota about 84 million years ago. The Niobrara consists of light-gray to yellowish-tan, blocky, calcareous marl. Fossils of ammonites, clams, fish (including sharks teeth), and sea turtles have been found in the Niobrara in the Rendezvous Region. The Pembina Member is a soft, black, noncalcareous shale that contains gypsum. It also contains numerous beds of yellowish-white bentonite clay (altered volcanic ash derived from volcanoes active in western Montana at that time), particularly at its base. The contact between the Niobrara and Pierre Formations is beneath the lowest bentonite band. Fish and mosasaur (large marine reptiles) remains have been found in the Pembina Member. This site was a promising fossil site until it was destroyed by road construction activity in 1996. Because this site is located on land owned by the State of North Dakota, destruction of the site violated North Dakota’s Paleontological Resource Protection Act. Collecting of vertebrate fossils at this site and any site on State of North Dakota land is prohibited without a permit issued by the North Dakota Geological Survey. View is to the west.

Exposures of the Carlile Formation in Pembina Gorge

Geology Site 3 - The Cretaceous-age, 90-million-year old, Carlile Formation is well exposed in this area of the Pembina Gorge. The Carlile Formation consists of soft, black, noncalcareous shale deposited in an offshore marine environment. At this locality, the Carlile is about 160 feet thick and is overlain by 30 feet of light-colored Niobrara Formation. The Carlile contains fossil shells of invertebrate animals and fish scales. It is the oldest rock formation exposed in North Dakota. View is to the east

Glacial Erratics in Little South Pembina River

Geology Site 4 - Glacial erratics, boulders carried to the Rendezvous Region by glaciers, are seen on the upland, glaciated areas of Pembina County and in the rivers. The composition of the erratics provides information about where they came from and the direction the glaciers moved. View is to the north.

Exposures of the Odanah Member of the Pierre Shale

in gravel pits

Geology Site 5 - The uppermost named member of the Pierre Shale, the Odanah Member, is exposed in this gravel pit. It was deposited in a shallow-water marine environment during the Cretaceous about 80 million years ago. The Odanah Member is a hard, siliceous, light-gray shale. Because of its hardness, it forms conspicuous cliffs and is quarried for road surfacing material. Fossils are scarce in the Odanah although oyster fossils have been recovered. View is to the northwest.

Drumlin North of Langdon

Geology Site 6 - Highway 1, four miles north of Langdon, cuts through a northwest-southeast trending, elongate hill called a “drumlin.” Drumlins are streamlined hills that were molded beneath sliding glaciers. The position of the drumlin indicates that the glacier flowed from the northwest to the southeast. View is to the north.

Esker West of Langdon

Geology Site 7 - Highway 5, four miles west of Langdon, cuts through a long, northwest-southeast trending, sinuous ridge called an esker. Eskers consist of sand and gravel that were deposited in streams and rivers that flowed in tunnels and cracks in glaciers. View is to the northwest.

Pembina Escarpment

Geology Site 8 - The Pembina Escarpment, an-east facing scarp that extends for many miles south of the Rendezvous Region, abruptly rises more than 250 feet above the glacial Lake Agassiz plain. Most of the escarpment consists of relatively soft Cretaceous marine shales which were eroded to initially form the scarp. Glaciers moving southward into the Red River Valley scoured the face of the scarp. The hard, resistant Odanah Member of the Pierre Shale, which occurs near the top of the escarpment, prevents rapid erosion of the scarp. View is to the west. (See Pembina Escarpment cross section diagram)

Sand Dunes West of Cavalier

Geologic Site 9 - Highway 5, about 11.5 miles west of Cavalier, cuts through sand dunes. These dunes were formed by winds transporting and depositing sediments derived from the Pembina Delta. The delta was formed where the ancient Pembina River emptied into glacial Lake Agassiz about 10,000 to 9,000 years ago. These sand dunes also began to form several thousand years ago. View is to the north.

Campbell Beach Ridge at Mountain

Geology Site 10 - The town of Mountain is built on one of the beaches, called the Campbell beach ridge, that formed along the shore of glacial Lake Agassiz about 10,000 years ago. The Campbell beach ridge represents a still stand of the water level in Lake Agassiz that probably lasted about 100 years. The Campbell beach ridge can be traced around the Red River Valley and is present on both the western and eastern sides of the Lake Agassiz plain in North Dakota and Minnesota. View is to the west.

Paleontology

Introduction

Paleontology is the study of ancient life (fossils) in contrast to biology the study of modern life. Fossils (from the latin word fossilis which means digging or to dig up) are the remains (shells, bones, etc.) or traces (tracks, burrows, etc.) of plants and animals preserved by natural causes in the Earth's crust (rocks, sediments, ice, lava, etc.). Although this definition appears rather straight forward it is not because some paleontologists believe that the remains must be prehistoric (at least 5,000 years old) before the remains should be considered fossils. Other paleontologists would apply a broader definition and include remains of plants and animals from historic times as fossils.* The definition of a fossil excludes objects constructed by humans which are called artifacts (arrowheads, pottery, baskets, houses, etc.). Artifacts are studied by archeologists not paleontologists.

*"If they stink, the remains belong to zoology, but if not, to paleontology."-Carl O. Dunbar

Paleontology is generally considered a sub-discipline of geology although many paleontologists have college degrees in one of the biological sciences. Most paleontologists are specialists and restrict their studies to a specific group of fossils such as clams, dinosaurs, sharks, leaves, insects, etc. Paleontologists study fossils to determine the kinds of plants and animals that inhabited the Earth at different times in the geologic past. Fossils are our primary means of documenting the history of life on Earth and should be viewed as objects of great scientific and educational value. Fossils also provide information about the types of climates and environments that existed in the past, and they are used to date and correlate rock units.

Paleontology of the Rendezvous Region:

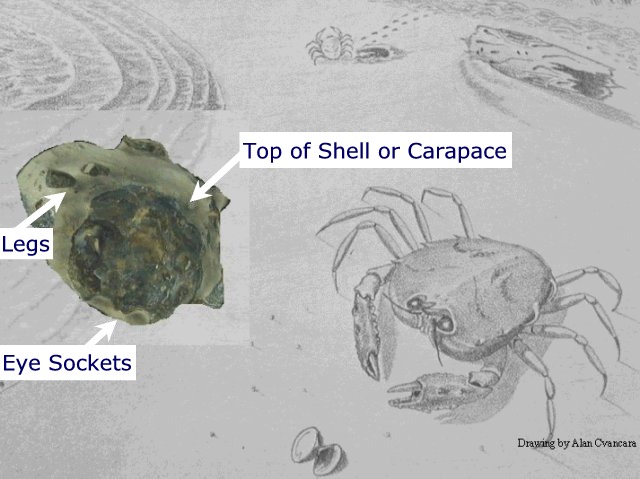

Rocks of the Carlile, Niobrara, and Pierre Formations are exposed in road cuts and along rivers in the Rendezvous Region. These rocks were deposited in subtropical to warm temperate seas, the Western Interior Seaway, which covered North Dakota during Late Cretaceous time from about 90 million to 80 million years ago (Map 4). Fossils of animals and plants that inhabited those seas are entombed in these rocks. Remains of marine reptiles (mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and turtles), fish (including sharks), and invertebrates (including clams, cephalopods, snails, corals, and crabs) have been recovered from the rocks.

Remains of plants and animals (including the woolly mammoth) that lived during the last Ice Age a few thousand years ago (Map 3) are also found in the Rendezvous Region.

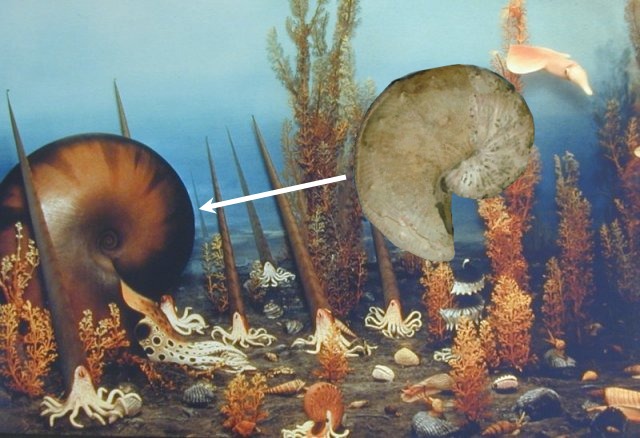

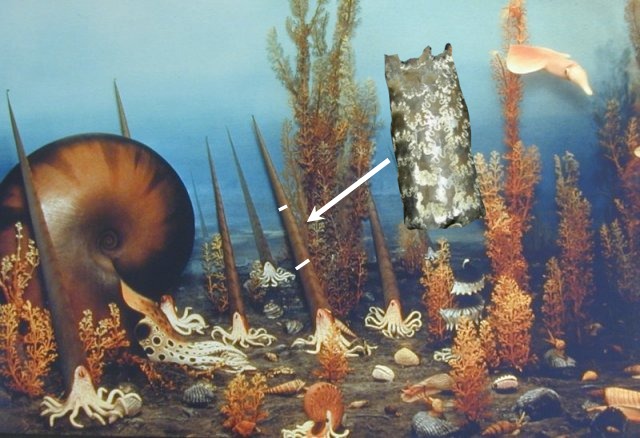

CRETACEOUS OCEAN FLOOR COMMUNITY

This picture of a diorama in the Smithsonian Institution shows many of the invertebrate animals that lived, at least part of the time, on the floor of the ocean that covered the Rendezvous Region during the Cretaceous.

Width 6 inches

Height .5 inch

Width .75 inch

Height 4 inches

Height 4 inches

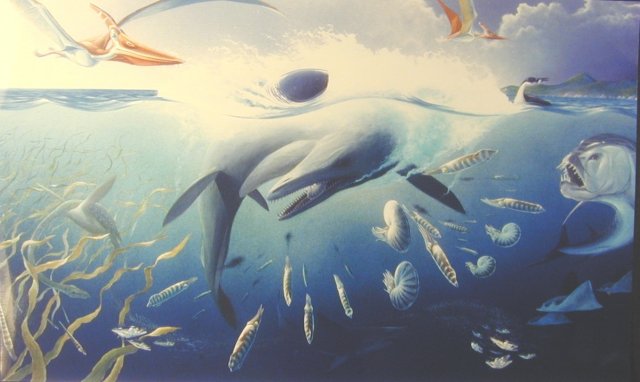

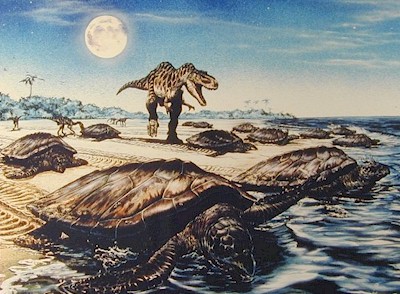

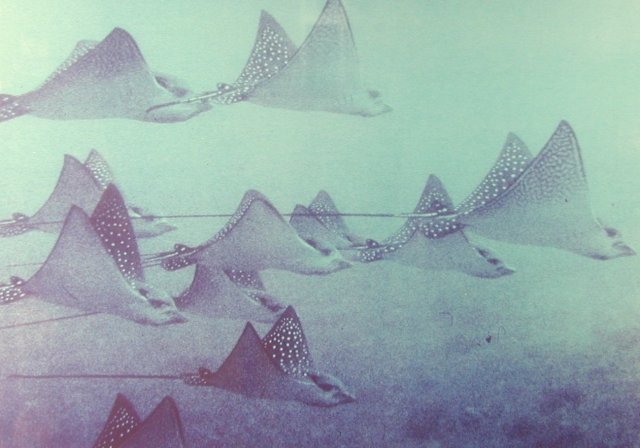

CRETACEOUS OCEAN COMMUNITY

This picture of a mural in the Pembina Sate Museum shows many of the animals that inhabited the Western Interior Seaway that covered the Rendezvous Region during the Cretaceous. The picture is based on fossils found in North Dakota.

Key to habitat reconstruction mural:

1) Mosasaur (Plioplatecarpus), a marine reptile; 2) Pterosaur, a flying reptile; 3) Plesiosaur, a marine reptile; 4) Seabird (Hesperornis); 5) Sand-tiger shark (Carcharias); 6) Cephalopods; 7) Salmon-like fish (Enchodus); 8) Rays; 9) Tarpon-like fish (Xiphactinus)

Hesperornis

5 feet tall

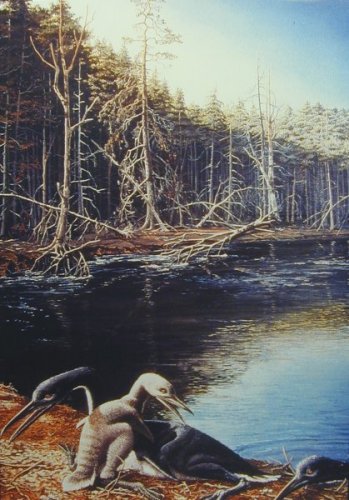

Painting of Hesperornis diving

Hesperornis was a large, up to about five-foot-tall, flightless seabird. It was equipped with sharp, pointed teeth and probably preyed on fish and squids underwater. Although it was incapable of flight, Hesperornis was a swift swimmer that could propel itself through the shallow coastal waters of the Pierre Sea with its powerful hind legs. Painting by Dan Varner.

Painting of an adult Hesperornis and hatchling on the shore of the Pierre Sea

Painting by Eleanor Kish

Toxochelys

(From Carroll, 1988).

Ptychodus

Squalicorax

Width .75 inch.

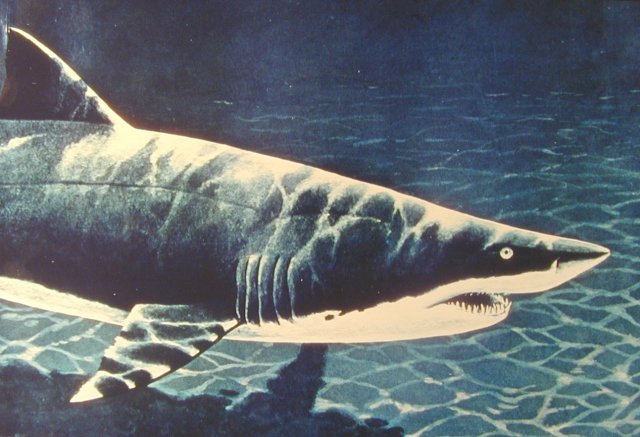

Painting of the living sand-tiger shark, Carcharias taurus

Several kinds of sharks inhabited the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous in the Rendezvous Region including a variety that was very similar to the living sand-tiger shark, Carcharias taurus shown in this painting. Painting by Richard Ellis

Plesiosaur

From Carroll, 1988 40 feet long

Painting of a Cretaceous underwater scene featuring a long-necked plesiosaur.

This painting of a Cretaceous marine habitat features one of the marine reptiles called a plesiosaur. Plesiosaurs grew to lengths of 40 feet or more. Plesiosaurs and mosasaurs were the main predators that lived in the Cretaceous seas. Another predator, a shark, is also shown in the painting. Plesiosaurs were not dinosaurs but became extinct at the same time as the last of the dinosaurs. Painting by Vladimir Krb

Stratodus apicalis

Xiphactinus

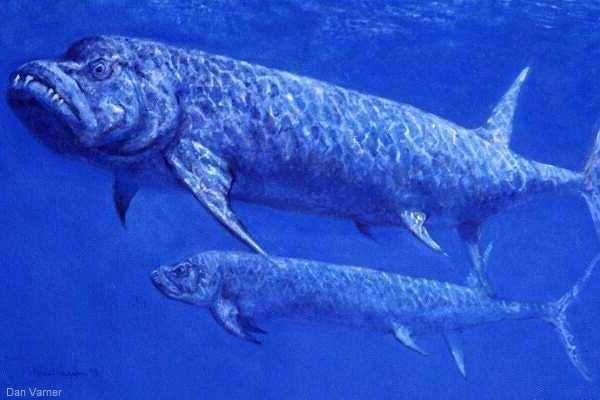

Painting of Xiphactinus

The tarpon-like fish, Xiphactinus, was one of the largest fish that inhabited the Pierre Sea. It grew to lengths of eighteen feet. Their large size, elongate bodies, powerful tails, and bulldog-like jaws suggest that they were efficient predators. Xiphactinus had large fangs at the front of the mouth probably used to strike or impale prey during initial attach. Painting by Dan Varner.

Plioplatecarpus

Painting of Plioplatecarpus

The mosasaur Plioplatecarpus was one of the reptiles that inhabited the Pierre Sea. Mosasaurs were huge animals, some up to 30 feet long, with long lizard-like bodies. Unlike their terrestrial lizard relatives, the limbs of mosasaurs were modified to form flippers. Mosasaurs swam by lateral undulations of the posterior part of their bodies and laterally compressed tails. Their flippers were used primarily for steering rather than for propulsion as the animal glided through the water. Mosasaurs were active predators and among the main carnivores in the Pierre Sea. They probably preyed on other mosasaurs, fish, turtles, and invertebrates. Although mosasaurs were not dinosaurs, they became extinct at the same time as the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago. Painting by Dan Varner.

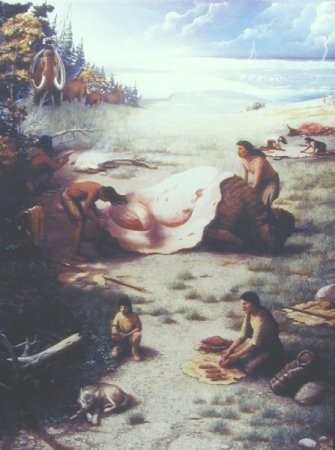

The Rendezvous Region at the end of the Ice Age

This picture of a mural in the Pembina State Museum is a scene of the Rendezvous Region at the end of the Ice Age about 11,000 to 10,000 years ago. A glacier is present in the back ground and glacial Lake Agassiz is forming in front of the glacier as the glacier melts. At this time, the Rendezvous Region was inhabited by woolly mammoths and bison. The first people to live in North Dakota migrated here about this time. They hunted the big game for food and clothing.

EXHIBITS:

Exhibits of fossils of the prehistoric life that inhabited the Rendezvous Region can be seen at the North Dakota Heritage Center, Bismarck; Pembina State Museum, Pembina; Icelandic State Park, Cavalier; Cavalier County Museum, Dresden; and the Morden Museum, Morden, Manitoba.

The Rendezvous Region Traveling Education Trunk is a cooperative project between the

North Dakota Geological Survey, North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department, and State Historical Society of North Dakota.