By John P. Bluemle

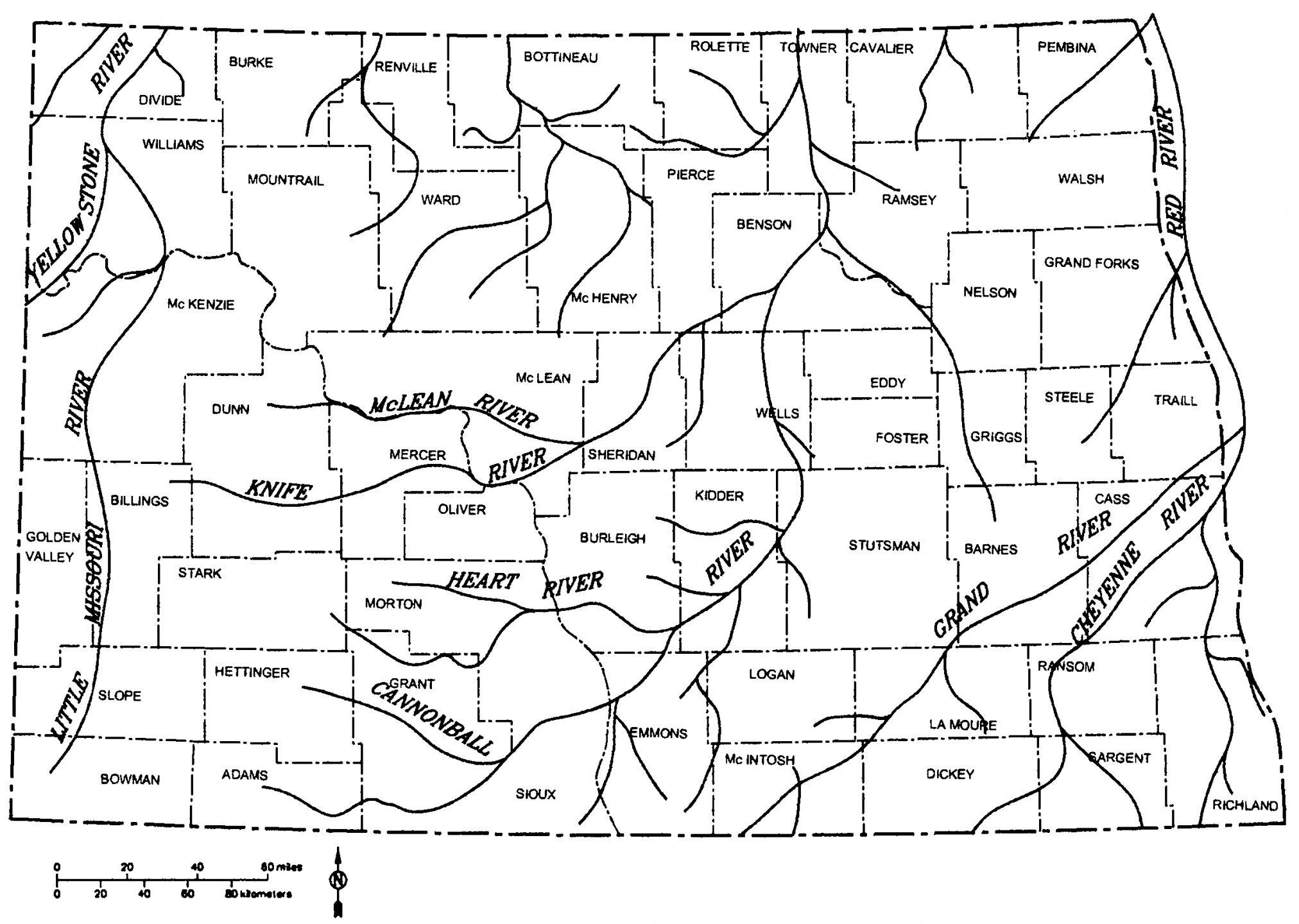

Before North America was first glaciated during the Ice Age about two million years ago, all of the rivers in North and South Dakota and eastern Montana drained northeastward into Canada to Hudson Bay. There was no Missouri River carrying drainage from the northern mid-continent to the Gulf of Mexico (my definition of the Missouri River requires that it flow to the Gulf of Mexico). Why is the modern situation so different than it was two million years ago?

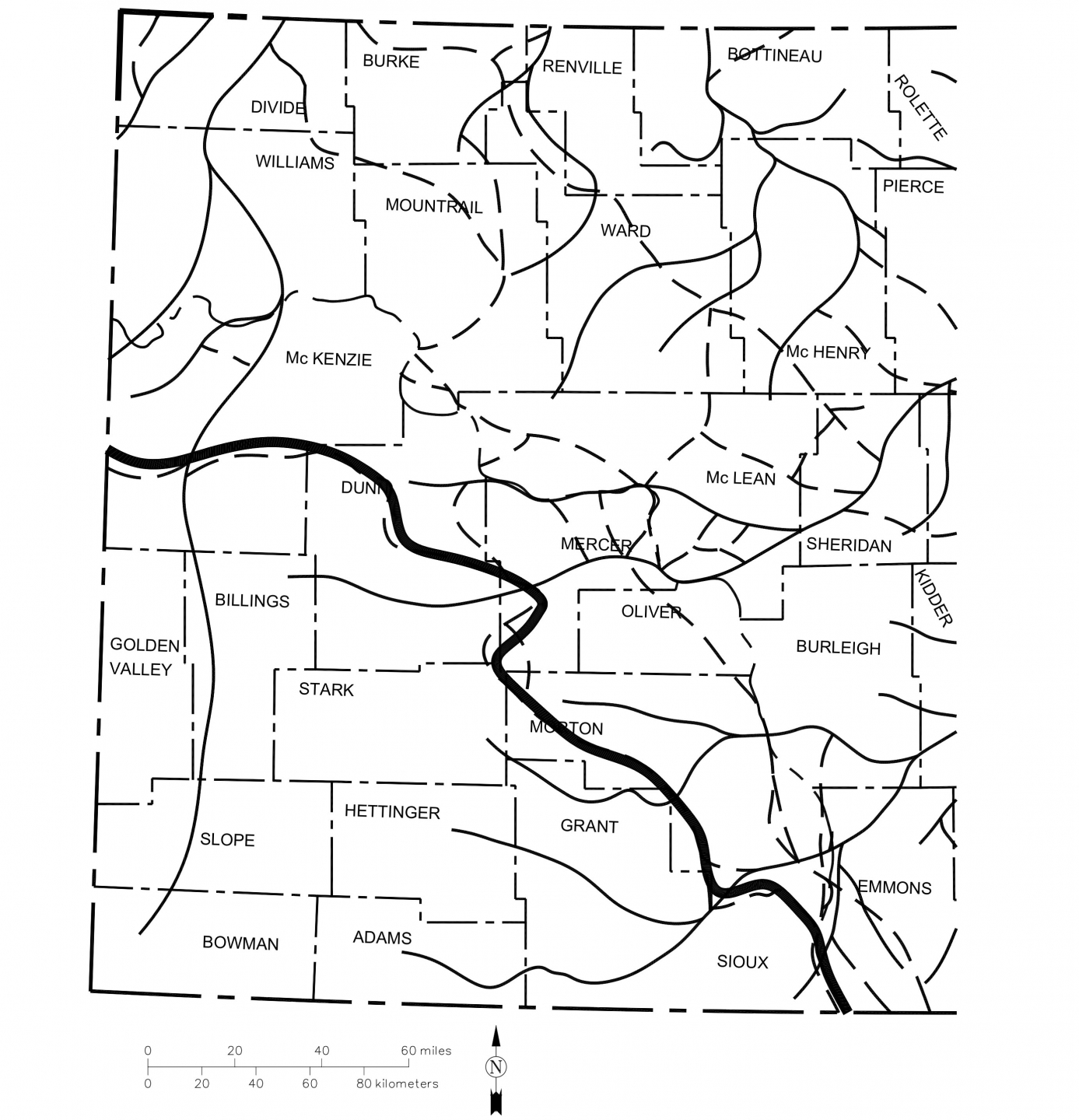

Schematic map showing a portion of the route of the preglacial “McLean River,” which flowed eastward through a broad valley that passed between Garrison and Riverdale, to the Turtle Lake area, and on into Sheridan County. When the McLean River valley was blocked by a glacier, a proglacial lake formed in the valley. When the lake overflowed southward from a point near Riverdale — at the site of the modern Garrison Dam — a narrow diversion trench was cut. The modern Missouri River flows through this diversion trench.

The modern Missouri River Valley in North Dakota consists of a number of "segments" of valley that are quite different from one another. Some of these valley segments are broad: six to ten miles wide from edge to edge, with gentle slopes from the adjacent upland to the valley floor. Others are narrow: less than two miles wide, with rugged valley sides. Generally, the wide segments trend west-east and the narrow segments trend north-south. There are a few exceptions - the Bismarck-Mandan area is one of them and I'll explain why shortly.

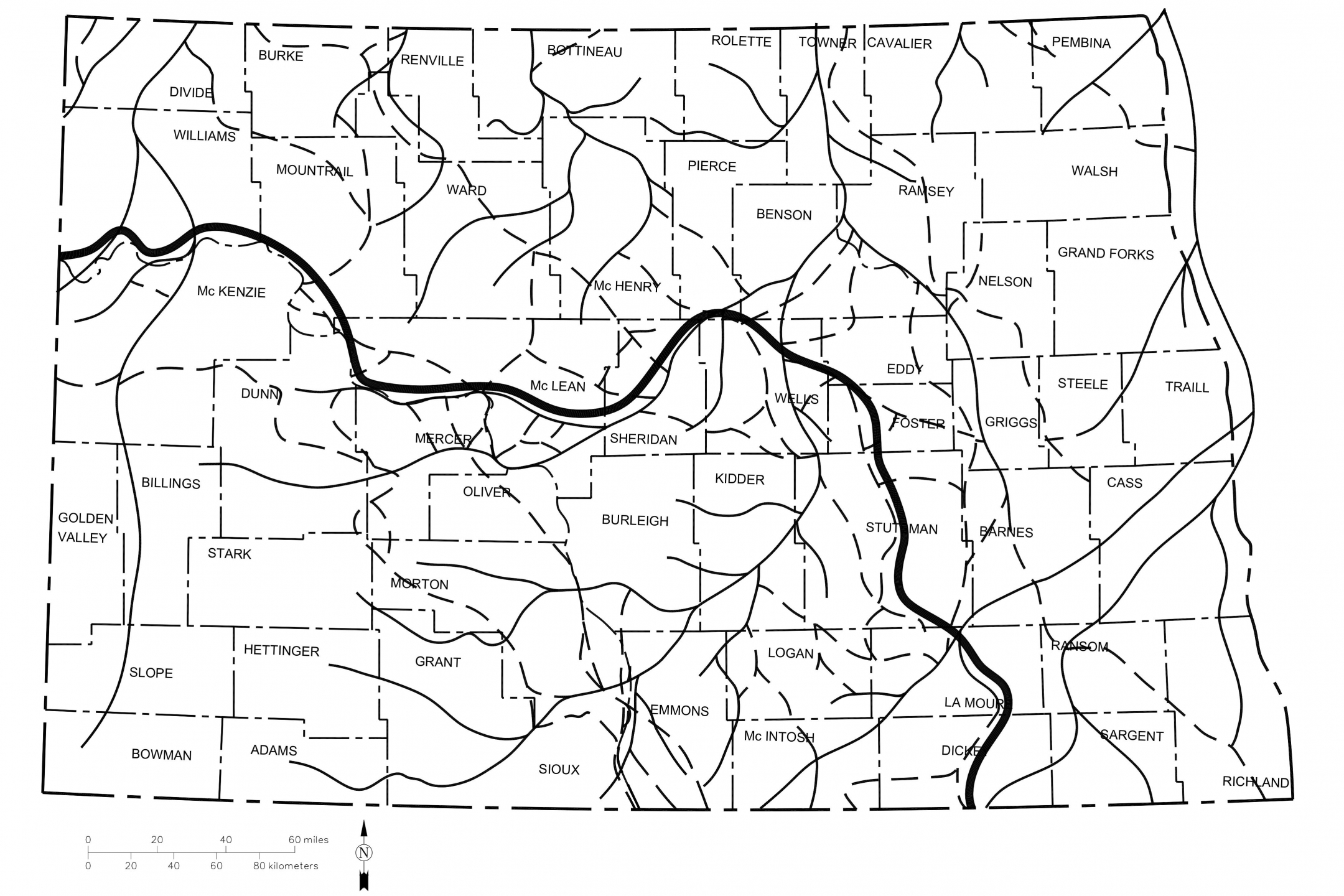

Map of North Dakota showing the drainage pattern prior to glaciation. All rivers flowed north or northeast into Canada. The Missouri River valley did not exist (except for short segments that correspond to portions of valleys such as the Knife and McLean River valleys — see text).

The west-east segments of the Missouri River Valley are wide because they coincide with much older valleys, some of which had already existed for a long time prior to glaciation. Old or mature river valleys tend to be broad with gentle slopes. Younger immature valleys are usually narrower with steeper sides.

For example, the 40-mile-long segment of the Missouri Valley upstream from Garrison Dam is quite wide. This part of the valley, which is now flooded by Lake Sakakawea, was once the route of a river that flowed east to Riverdale, continued eastward past Turtle Lake and Mercer, and flowed on into eastern North Dakota. For convenience, I'll refer to this east-flowing river as the "McLean River." The portion of the McLean River Valley east of U.S. Highway 83 is buried beneath thick deposits of glacial sediment. It's still a somewhat lower area - a kind of sag through eastern McLean County. A number of lakes - Turtle Lake, Lake Williams, Brush Lake, and others, are located in the sag. East of there the McLean River Valley is so deeply buried beneath glacial deposits that it is virtually impossible to follow it without drilling test holes to determine its location. Fortunately, we have drilled hundreds of such holes in our geologic studies of the glacial deposits and we have a good idea of the route the river followed into eastern North Dakota.

Another west-east trending segment of the modern Missouri River Valley is the one between Stanton and Washburn. This is an eastward continuation of the modern Knife River. Prior to glaciation, the Knife River flowed east past Washburn, turning slightly northeastward there. It joined the McLean River in eastern McLean County near the town of Mercer. The Knife-McLean River continued northeastward to the Devils Lake area, then north along the east side of the Turtle Mountains into Canada (remember, all of this was before North Dakota was glaciated).

View over the Missouri River south of Riverdale, McLean County, North Dakota (Photo by J. Bluemle).

Westward view of the Missouri River, 2 miles west of Washburn, North Dakota (Photo by J. Bluemle).

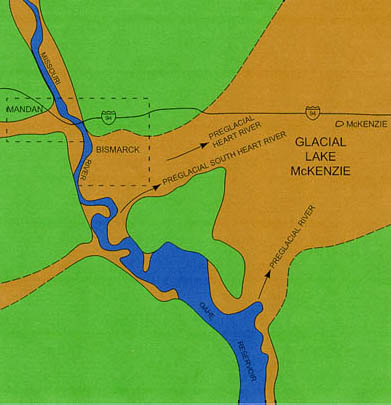

At Bismarck-Mandan the Missouri River Valley is only about two miles wide where Interstate Highway 94 crosses the river. On the south side of Bismarck, the valley broadens to about six miles wide, although it retains its steep western edge. The reason for this widening is that, prior to glaciation, the Heart and Little Heart Rivers, which today flow into the Missouri River (the Heart River enters the Missouri River at Mandan; the Little Heart enters about ten miles south of Mandan), joined a few miles east of Bismarck. The old, combined Heart-Little Heart valley still exists as the broad lowland south of Bismarck - a wide spot in the Missouri River Valley.

To summarize the situation at Bismarck-Mandan: the Missouri River Valley north of the two cities is much younger (formed during a glacial event, perhaps 25,000 years ago) than is the valley several miles south of the city, where it coincides with - crosses - the old, preglacial northeast-trending Heart-Little Heart valley.

I've been discussing several of the wide, east-west segments of the Missouri River Valley. Most of the narrow, north-south segments of the valley formed in places where glaciers diverted rivers southward. North Dakota was glaciated about a dozen times during the Ice Age and most of the glacial activity tended to be concentrated in the eastern and northern parts of the state. However, each time glaciers advanced southward through the Red River Valley and other parts of eastern North Dakota, they also expanded westward and southwestward, causing what had been northeasterly flowing rivers to be diverted along the western margin of the glacier. When the McLean River was blocked by a glacier in the Riverdale area midway through the Ice Age, a large, proglacial lake formed ahead (to the west) of the ice in the valley of the McLean River. This was the "original" Lake Sakakawea - an early ice-dammed lake that predated the Corps of Engineers version of Garrison Dam by a few hundred thousand years. Eventually, the proglacial lake overflowed (there was no spillway) just about where Garrison Dam is today, and the resulting flood quickly carved a narrow trench southward to the Stanton area (kind of an early Garrison Diversion Project - those glaciers moved slowly, but at least they got the job done!). But, at the same time this was happening, the Knife River Valley was also flooded, dammed by glacial ice in the Washburn-Wilton area. The lake in the Knife River Valley, in turn, spilled southward into the Burnt Creek-Square Butte Creek drainage, carving a narrow trench from just south of Wilton to Bismarck-Mandan. It's possible these events took place quickly - kind of a domino effect, but we don't really know.

View of the Missouri River, south of Bismarck (Photo by J. Bluemle).

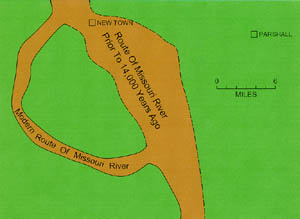

The youngest, and narrowest segment of the Missouri River Valley in North Dakota is in the New Town area between Four Bears Bridge and Van Hook Bay. As recently as 14,000 years ago, a glacier forced the river, which had been flowing through a broad valley now known as the "Van Hook Arm," into a new position a few miles farther west.

Schematic map showing the Missouri River Valley at Bismarck-Mandan. South of Bismarck, the valley is very wide because it corresponds to the old, northeast-trending preglacial valley of the Heart River. North of Bismarck-Mandan, the valley is narrow with quite steep sides. This portion of the valley was formed when an ice-dammed lake to the north in the preglacial Knife River valley overflowed from a point near Wilton. A similar ice-dammed lake existed in the Heart River Valley east of Bismarck — the glacial Lake McKenzie.

View looking north along the Missouri River, ten miles north of Bismarck. (Photo by J. Bluemle)

Schematic map showing the old route of the Missouri River at New Town (within the dashed lines) and the more recent route, formed when the glacier diverted the river farther southwest (within the solid lines). This diverted loop of the Missouri River is the youngest portion of its valley through North Dakota. It formed about 14,000 years ago.

What routes did previous Missouri Rivers follow through North Dakota on their way to the Gulf of Mexico? I'll mention only a couple of them. As I said, all of them flowed generally southward because the original, northerly routes of all other rivers into Canada were blocked each time glaciers advanced into the state. In eastern North Dakota, most of these early Missouri River valleys are buried today beneath thick layers of glacial sediment. One of them had a route that took it southward past Cooperstown and Valley City to the southeastern corner of the state.

At different times during the Ice Age, various routes were followed by the major river that drained the northern plains (the “Missouri River”) southward. The route shown here is problematical, although entirely possible and as good a guess as any of nearly countless other possible routes. Certainly the “Missouri River” followed routes similar to the one shown here (heavy, dark line) at various times during the Ice Age.

In western North Dakota, an early Missouri River was formed when a glacier advanced into the southwestern part of the state. A river flowed southeastward along the edge of the glacier, forming a valley from the area of the Killdeer Mountains, past Hebron and Glen Ullin, and on to the Fort Yates area. The resulting valley is a large one that probably served as the "Missouri" River for a much longer period than the modern Missouri River Valley, (at least up to now). Interstate Highway 94 crosses this old Missouri River Valley about halfway between Dickinson and Mandan.

To sum up: the modern Missouri River Valley is a "composite" of old, wide pre-glacial valleys and younger, narrower valleys that were cut at various times during the Ice Age. The parts of the Missouri River Valley that extend west-east are generally wider and these are the older segments. The parts that extend north-south are generally narrower and younger.

Even though many other earlier versions of the Missouri River existed during the Ice Age in eastern North Dakota, most of them were later buried beneath thick deposits of glacial sediment. The modern Missouri River Valley is simply the latest in a continuing series. After the next glacier has come and gone, the "new" Missouri River will undoubtedly follow a different route than it does today.

Each time North Dakota was glaciated, diversion trenches formed along the ice margin as it stood in various positions. In most of eastern and northern North Dakota, these diversion trenches, shown by dashed lines, are now buried beneath thick glacial deposits. However, some of them in the southeastern part of the state are still prominent features, valleys without rivers.

This map illustrates the southwestern most route of an early “Missouri” River (heavy, dark line) and is the modern Killdeer-Shields Channel, which extends from the Killdeer Mountains, southeastward to Sioux and Emmons counties.