By John W. Hoganson and Johnathan Campbell

Introduction

In the Spring of 1994, Roger Andrascik, Resource Management Specialist at Theodore Roosevelt National Park, contacted the North Dakota Geological Survey to see if we would be interested in conducting a study of the paleontological resources of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Like many federal agencies, the National Park Service is developing programs to characterize paleontological resources on properties they administer. At this time, funding had become available for paleontological studies of several national parks, including Theodore Roosevelt National Park. The paleontology of Theodore Roosevelt National Park was particularly poorly known because few paleontological investigations had been previously conducted in the park. The objectives of this proposed study would be to identify, map, and assess the significance of fossils and paleontological sites in the park. That information would be used in overall resource management planning. In 1994, the National Park Service and the Survey entered into a cooperative agreement to conduct an inventory and assessment of the paleontological resources of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Funding was available for 50 days of fieldwork for two people over a period of 2½ years. Field investigations for the project and laboratory curation of fossil specimens collected during the fieldwork were completed this year.

Figure 1. Location of North and South Units, Theodore Roosevelt National Park (H indicates location).

Theodore Roosevelt National Park consists of a North Unit, near Watford City (McKenzie County) and a South Unit, near Medora (Billings County) (Figure 1). Between the two units, 70,228 acres (about 110 square miles) of land are included in the park boundaries. The task of providing a meaningful paleontological assessment of the park initially seemed overwhelming because of the immensity of the park and the limited resources available to conduct the project. The ideal plan would have been to survey on foot the entire area of rock outcrop in the park. This was, of course, not practical and it was decided that the best approach would be to thoroughly survey selected one-square-mile sections. Sections selected for comprehensive fossil resource assessments were chosen primarily because of accessibility and extent of rock outcrops. All rock formations and stratigraphic levels were included in the survey. In this way, density of fossil sites per section and other findings could be applied to the entire park in a quasi-statistical way. Fossil sites were mapped and plotted on USGS 7.5-minute quadrangle maps. The actual collecting of fossil specimens was kept to a minimum to expedite the inventory. Only enough collecting was done to sufficiently characterize the sites.

Geology and Stratigraphy

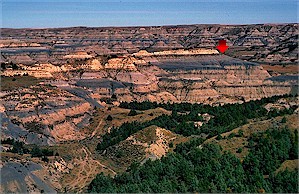

The badlands of Theodore Roosevelt National Park formed mainly through erosion by the Little Missouri River, have attracted geological interest since the days of the early scientific explorers primarily because of the well-exposed rock formations and the scenic beauty of the area. Two primary rock formations are exposed in the park, the Bullion Creek Formation and the overlying Sentinel Butte Formation (Figures 2 & 3)

Figure 2. Bullion Creek Formation exposed along the Little Missouri River in the South Unit. Arrow points to contact between the Bullion Creek Formation and the overlying Sentinel Butte Formation. The view is to the north. Cottonwood Campground is in the grove of trees on the east side of the river.

These rocks were deposited by fluvial and lacustrine systems during the Paleocene Epoch between about 60-55 million years ago when sediments were carried from the rising Rocky Mountains and deposited on the Central Plains. In the park, these formations are generally flat-lying and the stratigraphy is not confused by structural complexities.

The Bullion Creek Formation is exposed only in the South Unit of the park. It generally consists of brightly colored (yellows and tans) and poorly lithified claystones, mudstones, and siltstones with subordinate amounts of fine-grained sandstones and lignite (Figure 2). These sediments were deposited in a dynamic system containing rivers, streams, ponds, lakes, and swamps. The Bullion Creek Formation reaches a thickness of over 200 feet in the South Unit.

Figure 3. Sentinel Butte Formation exposed along the Little Missouri River in the North Unit. The view is to the west taken from near River Bend Overlook.

The Sentinel Butte Formation overlies the Bullion Creek Formation in the South Unit and is the only one of these two formations exposed in the North Unit (Figures 2 & 3). It generally consists of lithologies similar to the Bullion Creek Formation but usually exhibits somber gray to brown colors. Both formations were deposited in similar settings. A gray sandstone, that may attain a thickness of 100 feet in the North Unit, is present at the base of the Sentinel Butte Formation. The Sentinel Butte Formation can be over 700 feet thick in the North Unit and 300 feet thick in the South Unit. In isolated outcrops it is, in places, difficult to distinguish the two formations because dark-colored beds are sometimes present in the Bullion Creek Formation and light-colored beds are sometimes observed in the Sentinel Butte Formation.

In addition to color, several other characteristics are useful to help differentiate the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations in the park. The contact between the two formations is generally easy to recognize because it is usually at the base of a pink clinker bed called the HT Butte clinker. In places, the HT Butte lignite is at the contact and the contact is then placed at the top of the lignite (Figure 2).

Figure 4. Sentinel Butte bentonite/ash (arrow) and overlying "yellow siltstone" in the Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit. The view is to the east taken from Bentonite Clay Overlook.

A widespread ash/bentonite deposit called Sentinel Butte ash, at times 25 feet thick, occurs in the Sentinel Butte Formation in the North Unit (Figure 4). Also, the Sentinel Butte Formation generally forms steeper weathering slopes than the Bullion Creek Formation.

Fossil sites mapped in the park are tied to stratigraphic "marker beds". In the South Unit, the following stratigraphic references are used: 1) the contact between the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations at either the HT Butte lignite or clinker (Figure 2); and 2) the extensive fossil tree stump-bearing petrified wood bed near the base of the Sentinel Butte Formation (Figure 5). In the North Unit, the fossil sites are tied to: 1) the Sentinel Butte ash/bentonite bed (Figure 4); and 2) a bright yellow siltstone ("yellow bed") above the Sentinel Butte ash/bentonite (Figure 4).

Even though the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations are the primary fossil-bearing units in the park, other geologic units are present. On some of the higher hills in the North Unit, blocks of silcrete (silicified quartz siltstone) form lag deposits believed to be the Taylor bed of the Golden Valley Formation. Sand and gravel deposits unconformably overlie the Sentinel Butte Formation in many places in both the South and North Units. The age of the sand and gravel is unknown. Loess (wind-blown silt) veneers the surface in many areas of the North and South Units and glacial erratics found on the upland surfaces in the North Unit mark the maximum extent of glacial advance in that part of the state. Quaternary alluvium and colluvium are found along the Little Missouri River and the steep cliff faces and several terraces of alluvial deposits have been mapped along the Little Missouri River.

Paleontology

Paleocene-age continental rock formations in North Dakota have generally been considered sparsely fossiliferous. Our detailed study of ten square miles of the park (about 1/10 of the entire area of the park) suggests that both the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations are often quite fossiliferous, particularly with the remains of freshwater mollusks (snails and clams). We mapped 400 fossil sites in the ten-square-mile study area, which is an average of 40 fossil sites per square mile. Most of these sites are freshwater mollusk sites.

The most common kind of fossil found in the park is petrified wood. Petrified wood occurs sporadically at several stratigraphic levels in both the Sentinel Butte and Bullion Creek formations, but is most common in the lower part of the Sentinel Butte Formation, in most places about 20 feet above the contact with the Bullion Creek Formation. Because of the abundance of these fossils, it was impractical to map the location of all petrified wood sites. Unusual sites were mapped, such as where fossil tree stumps were found in growth position in the Petrified Forest Plateau area of the South Unit (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Fossil tree stumps in growth position in the lower part of the Sentinel Butte Formation, Petrified Forest Plateau, South Unit. The large stump in the foreground is 3 feet tall.

Forest conditions prevailed during the deposition of at least the lower Sentinel Butte sediments reflected by the prolific in situ petrified stumps found at that stratigraphic position in many areas of the South Unit. Some of these trees were huge, leaving stumps seven to eight feet in diameter. It is believed that most of these trees were conifers, although poor preservation has hindered specific identification of the wood types. The well-preserved specimen shown in Figure 6 is an exception. The tree stumps are generally fluted without roots. Lack of root preservation suggests that these trees were probably rooted underwater and were growing in a swampy environment, similar to the bald cypress today. The bases of these stumps are generally embedded in lignite also suggesting growth in an aqueous environment. Some of the fossil stumps and logs show evidence of damage by insects and birds (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Unusually well-preserved piece of petrified wood from the Sentinel Butte Formation. Width = 4½".

Figure 7. A petrified log in the Sentinel Butte Formation, South Unit, showing damage probably caused by birds.

However, only one insect fossil, a Coleoptera (beetle) was found during this study. Leaf fossils (angiosperm, ferns, etc.) are also found in the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations in the park (Figure 8). They can be found in most lithologies but preservation is best in clinkers and fine-grained sandstones. Fossil seeds, including Cercidiphyllum (katsura tree), were also recovered during this study. Fossil twigs, roots, and branches are found in the Taylor bed (Golden Valley Formation) in areas of the North Unit.

Figure 8. Leaf fossil in fine-grained sandstone, Sentinel Butte Formation, South Unit. Width = 2 inches.

Remains of freshwater mollusks are common in the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations in the park (Figures 9-12). These fossils can be found in most lithologies from carbonaceous claystone to medium-grained sandstone but appear to be most abundant in siltstone. They are so abundant at some localities that they form coquina beds. Freshwater mollusks are particularly abundant in the yellow siltstone about 20 feet above the Sentinel Butte ash in the North Unit (Figure 10). That mollusk fossil-bearing siltstone persists throughout most of the North Unit. Several taxa of snails (including Campeloma, Lioplacodes, Viviparus), mussels (including Pleiselliptio), and pill clams (including Sphaerium) were identified during this study (Figures 9-12). Small snail opercula were also found. Ostracodes, small bivalved crustaceans, were recovered from some sites.

Figure 9. Freshwater clam (mussel) in a Sentinel Butte Formation claystone. Width = 3 inches.

Figure 10. Freshwater snails in the "yellow siltstone", Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit.

Figure 11. Freshwater clams (mussels) and snail (Campeloma), Sentinel Butte Formation, South Unit. Width of largest clam = 2½ inches.

Figure 12. Pill clam (Sphaerium), Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit. Width = ¼ inch.

Vertebrate fossils were found at 51 sites: 23 in the South Unit and 28 in the North Unit. All but four of these sites are in the Sentinel Butte Formation. The most common vertebrate fossils are remains of crocodile-like creatures called champsosaurs (Figures 13 & 14). Because they are robust, champsosaur vertebrae are often preserved in Paleocene age rocks in North Dakota. Two champsosaur taxa were identified, the common Champsosaurus and the extremely rare Simoedosaurus. Two fairly complete Champsosaurus skeletons were discovered and excavated from the South Unit during this study, one from the Bullion Creek Formation and the other from the Sentinel Butte Formation. Champsosaurs were one of several extinct kinds of crocodile and crocodile-like creatures that inhabited the park during the Paleocene. Champsosaurs, although not true crocodiles, resembled in some ways the living, long-snouted gavial crocodilians. They grew to lengths of about 10 feet. Inhabiting ponds and swamps, they were probably aggressive underwater predators that fed on fish. This is suggested by the hydrodynamic shape of their bodies, powerful back legs, and long snouts lined with sharp, pointed teeth. It is believed that these animals would lie on the bottom of ponds waiting for prey. As a fish swam by, the champsosaur would lunge off the bottom with its powerful back legs and attack the fish.

Figure 13. Champsosaurus vertebrae weathering out of the Sentinel Butte Formation, South Unit. The rock hammer is 12 inches long.

Figure 14. Life restoration of Champsosaurus lunging off the bottom of a pond after a fish. Painting by Jerome Connolly, The Science Museum of Minnesota, St. Paul.

Figure 15. Crocodile scute (left) and tooth (right), Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit. Height of tooth = ¾ inch.

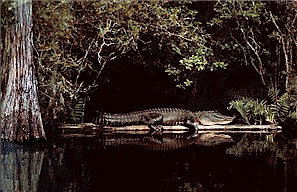

Figure 16. Photo of a living crocodile in a swampy habitat.

The remains of crocodilians, both crocodiles and alligators, were also found in the park. These finds, however, consisted only of disarticulated skeletal parts, mostly scutes (hard bony plates imbedded in the animal's skin) and teeth (Figure 15). The crocodile remains are probably Leidyosuchus, the common crocodile that inhabited North Dakota during the Paleocene. They grew to lengths of 12 to 14 feet. Like the champsosaur fossils, the crocodilian remains were found mostly in carbonaceous claystones and mudstones indicating that these animals lived and died in ponds and swampy habitats (Figure 16).

Figure 17. Johnathan Campbell restoring Protochelydra carapace collected from the Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit. Long dimension of carapace = 16 inches.

Other pond and near-pond-dwelling vertebrate animals are also represented by fossils in the park, including turtles and fish. Two kinds of turtles have been identified, the chelydrid (snapping turtle), Protochelydra (Figures 17 & 18), and the plastomenid (soft-shelled turtle), Plastomenus (Figures 19 & 20). One fairly complete Protochelydra carapace exhibits partially healed tooth puncture marks, probably indicating an attack by an alligator (Figure 18). At least two kinds of fish lived in the aquatic habitats at this time, Amia (bowfin) and Lepisosteus (gar). These taxa are represented only by skeletal fragments, mostly teeth and vertebrae. The vertebrae of another interesting animal, the giant salamander, Piceoerpeton, were found in the Sentinel Butte Formation.

Only four mammal fragments were discovered during this study, two teeth and two jaw fragments, all from the lower Sentinel Butte Formation in the North Unit. From these fossils, the lemur-like Plesiadapis, has been identified.

It should be noted that fossil Bison bones were often observed in Quaternary alluvial and colluvial deposits in both the North and South Units.

Figure 18. Protochelydra carapace showing healed tooth puncture marks on the posterior part of the carapace (same specimen as in Figure 17).

Figure 19. Johnathan Campbell collecting a Plastomenus carapace from the Sentinel Butte Formation, North Unit.

Figure 20. Restored Plastomenus carapace (same specimen as in Figure 19). Long dimension of carapace = 10½ inches.

Paleoenvironmental Interpretations

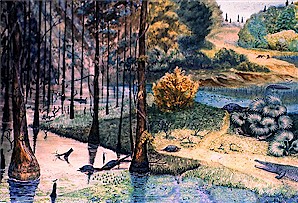

The fossils found in Theodore Roosevelt National Park and other fossil sites outside the park provide information about the environment and climate in North Dakota between about 60 million and 55 million years ago. During that time, sediments derived from erosion of the rising Rocky Mountains were carried to western North Dakota and were deposited in rivers, river floodplains, lakes, ponds, and swamps. These sediments, now at least partially lithified, are called the Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte formations. The climate was subtropical, probably similar to the southern part of the United States today. This hot and humid swampy lowland, at times containing extensive, well-established forests, provided a habitat for exotic plants and animals (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction of Theodore Roosevelt National Park during part of the Paleocene. This reconstruction by Bruce R. Erickson, Science Museum of Minnesota, St. Paul, is based on fossils found in the Bullion Creek Formation at the Wannagan Creek fossil site, just west of the South Unit.

Invertebrate animals, including pill clams, mussels, snails, insects, and minute crustaceans, lived in rivers, streams, ponds, and swamps. Many kinds of vertebrates also lived in and near these aquatic habitats. The primary predators were crocodiles, alligators, and champsosaurs. The crocodiles and alligators preyed on turtles and the champsosaurs and snapping turtles preyed on fish. In turn, the fish preyed on the mollusks and insects in the ponds. Lush forests containing ferns, cycads, figs, bald cypress, Ginkgo, katsura, Magnolia, sycamore, giant dawn redwoods and other subtropical plants flourished at times in western North Dakota. Insects and birds lived on and ate these plants. Lemur-like mammals inhabited the swampy woodlands. Mammals were beginning to become established during this time because the extinction of the last of the dinosaurs had occurred just a few million years earlier.

Geology Exhibit Planned for Park Visitors Center, Medora

Under the direction of Bruce Kaye, Chief of Interpretation at Theodore Roosevelt National Park, work has begun on an exhibit to provide an interpretation of the geology and paleontology of the park. That exhibit will be installed at Medora in the Park Visitor Center at the entrance to the South Unit and will include many of the fossils collected in the park during this study. The most spectacular of those fossils will be a restored three-dimensional skeletal mount of one of the champsosaurs excavated in the South Unit (Figure 22). The exhibit will also include restored turtle fossils and examples of other vertebrate, invertebrate, and plant fossils found in the park.

The following photographs (22a - 22f) are of the collection and restoration of one of the fairly complete Champsosaurus skeletons found in the Sentinel Butte Formation, South Unit.

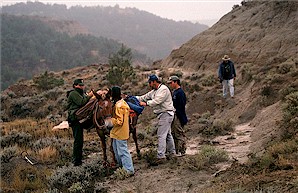

Figure 22a. National Park Service mule, "Bo", used to carry supplies and equipment into the remote excavation site.

Figure 22b. Champsosaur skeleton being encased in a large plaster field jacket at the excavation site.

Figure 22c. Field jacket containing champsosaur skeleton at the excavation site.

Figure 22d. Field jacket containing champsosaur skeleton being air-lifted from the excavation site. Photograph by Bruce Kaye, Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

Figure 22e. Champsosaur skeleton still in the plaster field jacket being worked on by Johnathan Campbell in the Survey's paleontology laboratory at the Heritage Center.

Figure 22f. Backbone of the champsosaur being reconstructed by Johnathan Campbell in the Survey's paleontology laboratory.