By Bob Biek

A concretion is a clearly bound body of rock within generally softer enclosing sediments of the same composition. The term comes from the Middle English concret, itself derived from the Latin concrescere, meaning to grow together or harden. Concretions form by the selective precipitation from groundwater of dissolved minerals, most commonly calcium carbonate, the stuff of which limestone is made and an important component of concrete, toothpaste, and a host of other products. Siderite (iron carbonate or "ironstone") is also an important cement. As these minerals precipitate, they fill in pore spaces between grains of sediment thereby cementing them together. Concretions can be massive and structureless, or they may preserve fossils or internal sedimentary structures such as crossbeds.

Nodules are hard bodies of rock similar to concretions, though of different composition than the sediments that contain them. The term nodule derives from the Latin nodulus, a diminutive of nodus, meaning knot. Nodules may also form by the selective precipitation of dissolved minerals that completely replace the original sediment, though some, such as siderite nodules, may form from a gel precipitated under reducing conditions.

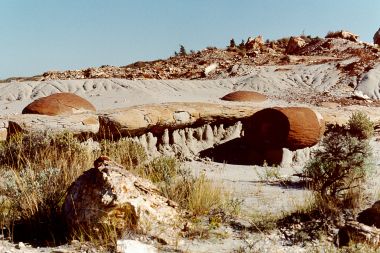

Two-foot diameter concretions from the Bullion Creek Formation, Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

Concretions in the Sentinel Butte Formation, Lake Sakakawea.

Small stem-cast concretion. (Photos by John Bluemle).

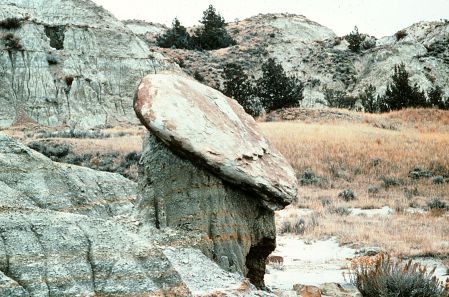

Sandstone concretion shielding pedestal of softer sediments, Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

Iron-stained sandstone concretions in the Bullion Creek Formation, Theodore Roosevelt National Park. (Photos by John Bluemle).

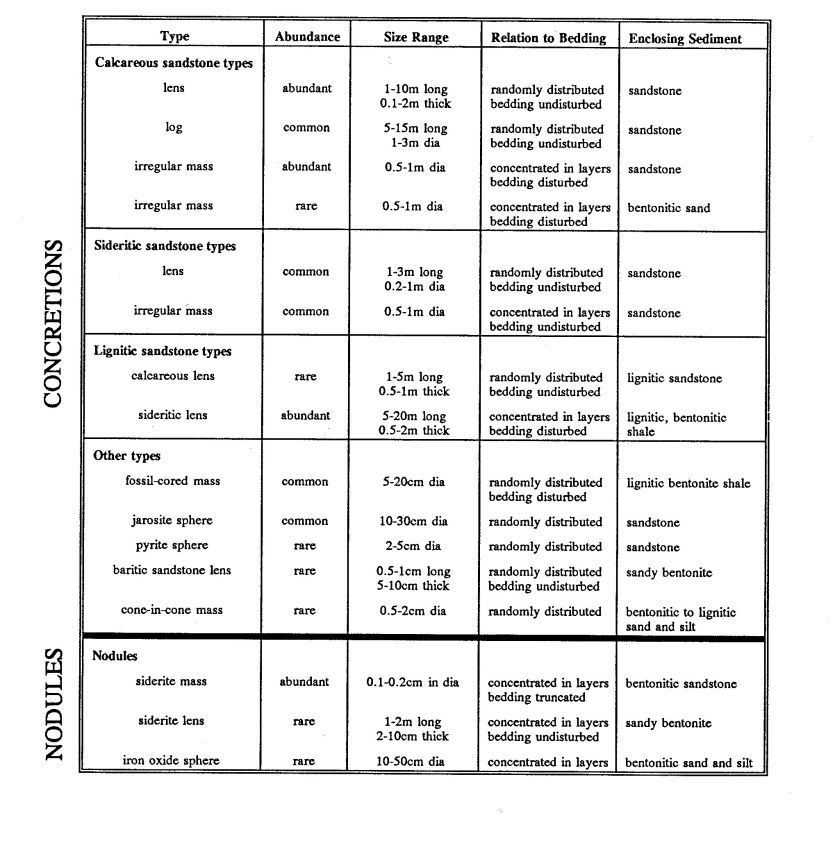

Classification

Although there is no comprehensive classification scheme for the great variety of concretions and nodules found in North Dakota, such a scheme would have to take into account three basic factors: shape, composition, and cementing agent. Such a scheme was developed for concretions and nodules of the Hell Creek Formation by Groenewold (1971).

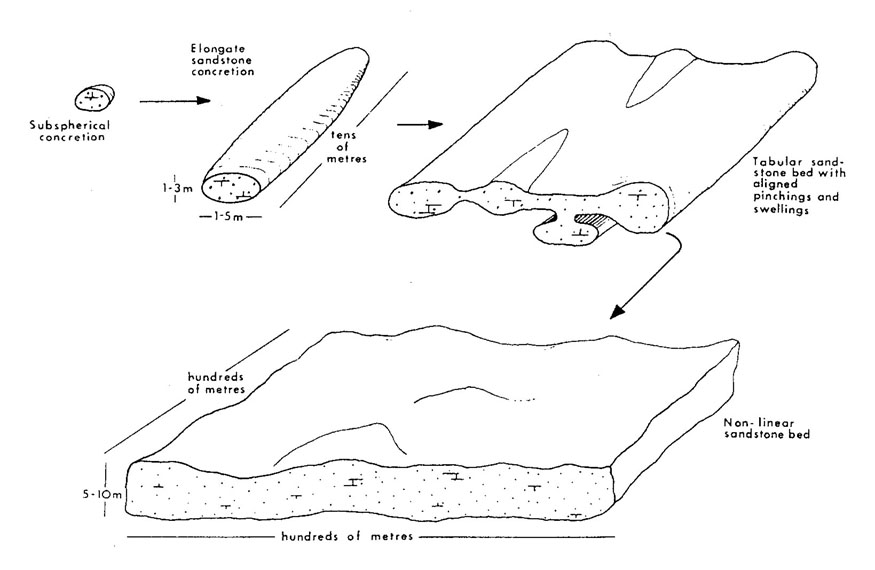

Sequence of forms developed by continued sandstone concretion growth. All four types, with many intermediate shapes, are present in southwestern North Dakota. From Parsons (1980).

What follows is a discussion of three types of concretions and nodules that I find particularly interesting, and that illustrate the diverse nature of shape, composition, and formation.

Sandstone Logs

Sandstone "logs" are elongate sand bodies that have been cemented, principally by calcium carbonate, to form log-like concretions (they are not petrified wood logs, though some could be so mistaken at a distance). The elongate form of the concretions results from preferred growth parallel to the direction of paleo-groundwater flow. They are common in channel sands of the Cretaceous Hell Creek and overlying Paleocene formations and are typically 1 to 3 meters (3 to 9 feet) in diameter and 5 to 15 meters (15 to 45 feet) in length. Most are oval in cross-section, though they may be circular or grade into sheet-like forms. Bedding and other sedimentary structures are usually well preserved in these concretions. In a detailed study of elongate concretions in Adams County, North Dakota, Parsons (1980) found that sandstone "logs" may be just an intermediate stage of complete lithification of an entire sand bed. As the "logs" grow, they can coalesce, ultimately forming a broad, tabular sandstone body, such as those that cap many of the buttes of southwestern North Dakota. These sandstone logs thus may represent the initial stages of lithification of some sandstones.

Oval and log-like sandstone concretions in the basal sandstone of the Sentinel Butte Formation at the Petrified Forest Olateau. Petrified stumps in the foreground and on the ridge in the distance have been let down from erosion of the overlying petrified wood beds. (Photos by John Bluemle).

At the microscopic level, Groenewold (1971) noted that sandstone "logs" from the Hell Creek Formation differ from their unconsolidated host in that relative to the concretion, the enclosing sediments often have more clay, chert, and volcanic materials. That these materials are either highly altered in, or absent from, the concretions, suggests that they have been partially or totally replaced by cementation.

Siderite Nodules

Siderite or "ironstone" nodules are heavy, dark brownish-black nodules that occur as small, isolated spheres, through complex rounded forms, to thin beds tens of feet long. They often form an erosion-resistant armor on badland slopes, where their black color contrasts sharply with the gray, clayey, eroded sediments out of which they weather. Siderite nodules are typically found in lignitic bentonitic, sediments and are often concentrated along certain horizons. They are especially common in the Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation.

Siderite nodules in the Hell Creek Formation. These dark-colored, heavy, iron-carbonate nodules often form an erosion-resistant armor on badlands slopes. Photo by Ed Murphy.

The outer rind of siderite nodules is often weathered to dark brown limonite, a "catch-all" name for relatively soft, complex mixtures of iron oxides and hydroxides. Underneath the weathered rind, nodules are dark purplish black in color, probably due to increased manganese content. Most nodules are characterized by a pattern of polygonal ridges, sometimes with raised welts at the center of each polygon, aptly described as "alligator skin".

Abundant field evidence - including truncated but otherwise undisturbed bedding around the nodules, and soft sediment deformation -indicates that the nodules formed contemporaneously with sedimentation (Frye, 1967), not later as in the case of the sandstone "logs" discussed above. The nodules probably formed at the bottoms of shallow ponds or lagoons, perhaps as a gel. In some cases, minor wave action rolled the gel, thus incorporating sand and fossil fragments or even breaking the gel into pieces now preserved as a sideritic conglomerate. The source of the iron may simply have been the abundant clay itself. Surface films of iron oxides are common on clay particles. If these particles are deposited in a reducing (oxygen-poor) environment, the iron may return to solution and be deposited as siderite.

Siderite nodule with characteristic "alligator skin" surface. This pattern of ridges and raised welts may have resulted from the solidification of an iron-carbonate gel. Photo by Ed Murphy.

Fossiliferous Concretions

Fossiliferous, carbonate-cemented concretions of the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation are well known for their exceptional molluscan fauna (bivalves, gastropods, and ammonites). In an effort to understand the chemical and physical processes responsible for concretion formation, Carpenter et al. (1988) studied changes in trace element and isotopic compositions between successive concretionary layers. Their results are fascinating.

The concretionary cements record the chemical signature of regional geologic events, including the initial shallow burial of concretionary sediments in a shallow marine environment, followed by deltaic progradation, relative sea level rise, and finally continued progradation of deltaic sediments. These conclusions are supported by independent sedimentologic and stratigraphic studies that show that the Fox Hills Formation is part of a regressive, marginal marine sequence.

I find concretions and nodules interesting precisely because they are different than what surrounds them. They stand out in a crowd: they are the classic, restored, old car in a long line of look-alike modern automobiles; the double play that everyone yearns for at a baseball game; the sparks from a campfire. Concretions and nodules exist in fantastic variety in North Dakota. They are most easily seen in areas of badland topography, and in fact, add much to the character and intrigue of such places, but those with a sharp eye can find them throughout the State.

Cannonballs

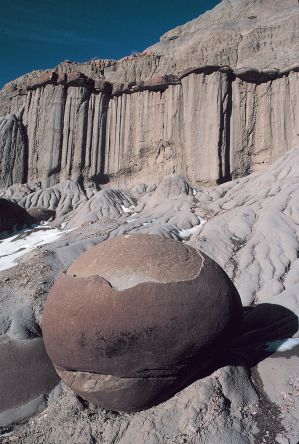

Among the more unusual concretions are "cannonballs," from which the Cannonball River, the town of Cannon Ball, and a host of proprietary Cannonball names are ultimately derived. "Cannonballs" are large, spherical sandstone concretions. They are common though not abundant in the Cannonball and Fox Hills Formations in Morton and Sioux counties and can be found in badland areas farther west, (Perhaps cannonballs are even more common as lawn and driveway ornaments in the Bismarck-Mandan area!) They are seldom greater than two to three feet in diameter. Like most other concretions, they are more resistant to weathering than enclosing sediments and often can be found at the base of slopes.

The cannonballs formed by cementation, with calcium carbonate being the principal cementing agent They may contain a small nucleus of organic material (a shell or plant fragment). Their spherical form suggests that growth was unconstrained by primary sedimentary structures or fabrics, such as would be the case for more flattened or irregularly shaped concretions.

A spherical concretion in the Sentinel Butte Fm., Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Note differences in weathering (castellate = vertical columns, rill = slope in foreground, exfoliation = concentric peeling of concretion). Photo by Ed Murphy.

References Cited

| Carpenter, Scott J., Erickson, J. Mark, Lohmann, Kyger C., and Owen, Michael R., 1988, Diagenesis of fossiliferous concretions from the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation, North Dakota: Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v. 58, no. 4, p. 706-723. |

| Franks, P.C., 1969, Synaeresis features and genesis of siderite concretions, Kiowas Formation (Early Cretaceous), north-central Kansas: Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v. 39, no. 3, p. 799-803. |

| Frye, Charles, I., 1967, The Hell Creek Formation in North Dakota: Unpublished UND Ph.D. Dissertation, 411 p. |

| Groenewold, Gerald H., 1971, Concretions and nodules in the Hell Creek Formation, south-western North Dakota: Unpublished UND M.S. Thesis, 84 p. |

| Jacob, Arthur F., 1973, Elongate Concretions as Paleochannel Indicators, Tongue River Formation, (Paleocene), North Dakota: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v.84, p. 2127-2132. |