By John P. Bluemle

If you find it hard to imagine that during much of its geologic past North Dakota was covered by shallow seas, or more recently was buried under several thousand feet of glacial ice, then you will probably find it no easier to picture our state as densely forested. Yet during the Paleocene epoch, between about 67 and 55 million years ago, western North Dakota was home to a subtropical to temperate forest with trees up to 12 feet in diameter and over 100 feet tall. During this time, western North Dakota must have looked much like coastal Georgia or Mississippi, with meandering rivers, everglade-like swamps, and vast, forested floodplains.

Petrified trees, stumps, and logs provide some of the most spectacular evidence for this ancient landscape. North Dakota's Paleocene-age rocks contain most of the petrified wood found in the state. These are the rock layers exposed in the badlands and elsewhere — the Sentinel Butte and Bullion Creek Formations, but petrified wood is also common in the slightly older Hell Creek Formation and in all younger bedrock units. The petrified wood occurs as entire logs, stumps that still stand upright where they once grew, and as scattered limbs and fragments. Some localities contain so much fossil wood that they can be termed petrified forests. Petrified wood is widespread in western North Dakota, and pieces of it can also be found in gravels in the glaciated portion of the state. It is commonly found in badlands areas, where entire logs and even upright stumps are exposed.

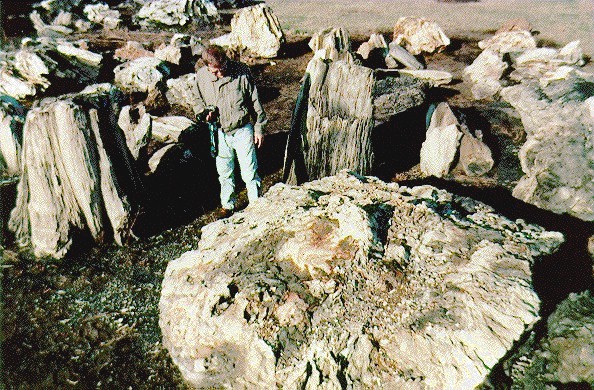

Geologist with a collection of stumps from the Sentinel Butte Formation near Dickinson

Petrified wood forms by the gradual mineral replacement of the organic material as it lies buried underground. Petrification requires rapid burial of the wood to prevent normal decay. This can happen, for example, as rivers overflow their banks, burying the forest floor under a layer of sand and silt, or when forests are covered by volcanic ash. After burial, mineralized groundwater begins to seep through the wood, coating cell walls and filling the intercellular cavities. Sometimes the original cellular structure is obliterated and what remains is simply a cast of the original log; other times, growth rings, bark, knots, and even cellular structure is preserved with remarkable fidelity. This later, more detailed preservation is possible because silica and other inorganic molecules are much smaller than organic molecules; rather than "molecule for molecule" replacement, the organic molecules are actually coated and surrounded with silica. Small amounts of impurities add color to the fossilized wood: yellow, brown and red indicate iron; black and purple take their hue from carbon or manganese.

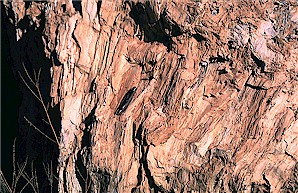

Part of a petrified stump near Medora, North Dakota. (Photo by J. Bluemle)

North Dakota petrified wood is variously preserved, from specimens that are well silicified, to splintery, and even grading to lignite coal (coalified trees). The degree of petrification can even vary within a single specimen; individual stumps or logs sometimes contain both well-silicified and coalified parts. Most North Dakota petrified wood is brown or tan on weathered surfaces and dark brown where fresh, but colors range from white to gray, sometimes with streaks of black. Sometimes, cavities in the wood are encrusted with chalcedony and lined with quartz crystals. Often, because they were compressed and flattened by the weight of overlying sediments, the logs are oval in cross-section.

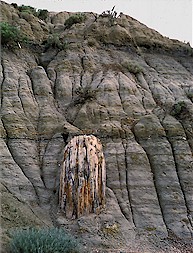

Petrified stump in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. (Photo by J. Bluemle)

The best-known petrified forest in North Dakota is found in the South Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. There, coniferous stumps from two successive forests have eroded out of the Sentinel Butte Formation. These trees are related to the modern Sequoia; some stumps are up to 12 feet in diameter. The stumps are still upright in the place where they grew 55 million years ago in a coastal floodplain environment. The stumps were preserved as floods inundated the forest floor, burying the bases of trees; the unburied trunks and branches simply decayed away. Often the stumps sprout from a lignite bed or paleosol horizon which itself marks a former forest or swamp floor.

Petrified stump near Jones Creek in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. (Photo by J. Bluemle)

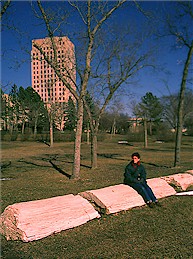

Another petrified forest is found in the Taylor area and well-silicified stumps are common in fields in the Amidon area, where they are often piled in the corners of fields. In 1990, when the level of Lake Sakakawea dropped precipitously, a large number of petrified logs were found weathering out of the Sentinel Butte Formation in Mercer County. The logs were probably transported to their present location by flood waters and subsequently buried. The logs are believed to belong to the genus Metasequoia, the dawn redwood. This type of tree was first discovered from fossils in 1941 and was believed to be extinct until living trees were discovered in south-central China in 1945. Today, the dawn redwood is widely used as an ornamental tree. One 80-foot-long log (and two stumps from the Amidon area) are now displayed on the North Dakota State Capitol Grounds.

Petrified log displayed at the North Dakota State Capitol grounds.

During the construction of Interstate 94 west of Dickinson, a 120-foot-long, petrified "redwood" log six feet in diameter was uncovered. It was offered to nearby towns as a tourist attraction, but was reburied when no one wanted it. Perhaps no one offered it a home because petrified wood is so common in southwestern North Dakota. Petrified wood is often used in landscaping, and many driveways and flower beds are lined with or centered around fine specimens. Petrified wood is locally so common that some farmers find it a nuisance and pile it up along fence rows, much like their counterparts in the east pile up glacial erratics. A Petrified Wood Park was even built in Lemmon, South Dakota. The brainchild of O.S. Quammen, the park was completed in 1932 and was built mostly with petrified wood collected in North Dakota.

In addition to Metasequoia, we know some of the other ancient trees that grew in North Dakota in the geologic past. They are known primarily through studies of fossil pollen and the recognition of the clear and delicate imprints of leaves in mudstone, siltstone, and carbonaceous paper shales. For example, remarkably preserved petrified cones of Sequoia dakotensis, silicified pods of the extinct Katsura tree, the tree fern Tempyska, and Osmundites are also found with petrified wood in the Cretaceous-age Hell Creek Formation. Forests as luxuriant and varied as those now growing in the southeastern United States spread eastward across North Dakota following the retreat of the Cannonball Sea. Cypress, black spruce, tamarack, and cedar grew in swampy areas. Plants with deciduous leaves also flourished. They are represented by poplar, ginkgo, hazelnut, oak, walnut, sycamore, box elder, elm, maple, birch, alder, hickory, dogwood, buckthorn, viburnum, witch hazel, horse chestnut, bittersweet, and many others.

North Dakota's ancient forests, with huge stumps and tree trunks, now form stunning landscapes of stone in the wildly eroded badlands of southwestern North Dakota. There, they mingle with modern, fragrant junipers, sagebrush, prickly pear cactus, and other hardy plants.